The Promise That Prevents Us From Reading

Friday Footnotes #14

Welcome to Friday Footnotes, a weekly newsletter from Storygram Parents. It’s even got pictures 🙌

Each week I touch on reading, parenting, motivation, children’s books, education, writers, and whatever else catches my attention. Enjoy!

This week’s footnotes 🧐

The Promise That Prevents Us From Reading

Each morning, I take my dog, Archie, for a walk to a nearby park. I live in London, and probably see a hundred people the moment I step out of my door!

There are the students of questionable fashion (or fashionably questionable students) heading to Chelsea College of Arts. There are grey-suited, grey-faced folk, shoes clipping importantly on the ground as they talk loudly into their phones. There are Italian families on tour, four abreast, walking unbelievably slowly.

After hundreds of these short journeys, there is one pet peeve (hah) that occurs reliably enough. At a particular junction, my path crosses a flow of human traffic, all heading somewhere with purpose. Without fail, they plough on through, forcing me to wait for them.

I can be painfully polite at times, which I’m sure is the sort of behaviour that causes Brits to have heart disease. I wait: patient, demure, saint-like — yet with daggers in my heart. Archie looks at me balefully. “Alpha male, I don’t think,” he says.

(I’ll get to the bit about reading shortly).

The average person1 today is so intent to get to their destination that any pause or detour seems a huge inconvenience. Even, I accept, when walking my dog. I just want him to do his business so I can get back to my business.

Here’s my half-baked hypothesis for the week: we stopped reading books2 because books don’t take us in a straight line to our destination.

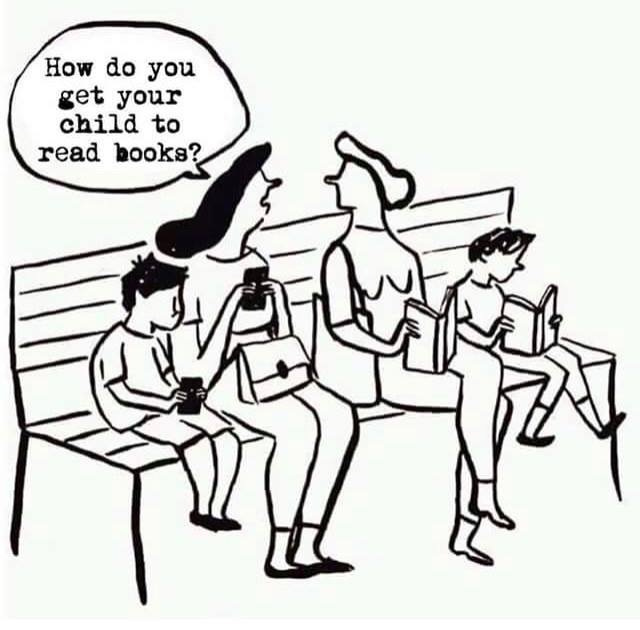

Yes, I know it’s the damn phones. Obviously.

But the allure of phones is not simply dopamine. It is also the promise. There is a promise that every time we unlock the screen, we will learn, be entertained, and feel loved. That something will happen. The phone provides a counterfeit shortcut to our heart’s desires. In that respect, it is the ultimate productivity tool3.

But instead of settling for the status quo (whether that’s walking the same route to work, reading only books that offer self-improvement, or looking to our phones for joy) we can become inquisitive and open-minded. We can allow detours, observing the journey and looking around us at new things. We can allow friction in numerous ways that adds colour back into our lives.

Reading fiction might not get you from A to B in the quickest time. It might not help towards your specific leadership goals, or teach you how to train your puppy. But instead of going from A to B, you might discover C — an altogether more tasteful destination, with fewer lager-louts. It might teach you the more subtle facets of leadership — care, attention, heroism, empathy, wisdom. It might not teach you anything about puppies at all. But you will be happier, and your puppy will be happier as a result. Take it from Archie.

Can I ask a favour? 🙏

Please comment, share, or like our articles… it helps the algorithm make good choices 😜

Perhaps you can think of one parent you could send the link to? Thank you so much!

The Dual Coding Delusion

This week’s recommended read is The Dual Coding Delusion, from David Didau.

David’s Substack (The Learning Spy) is fascinating and insightful. “A sharp, provocative dispatch from the front lines of education, where ideas are tested, myths are challenged, and nothing is taken for granted.”

Like Myth Busters, but for education.

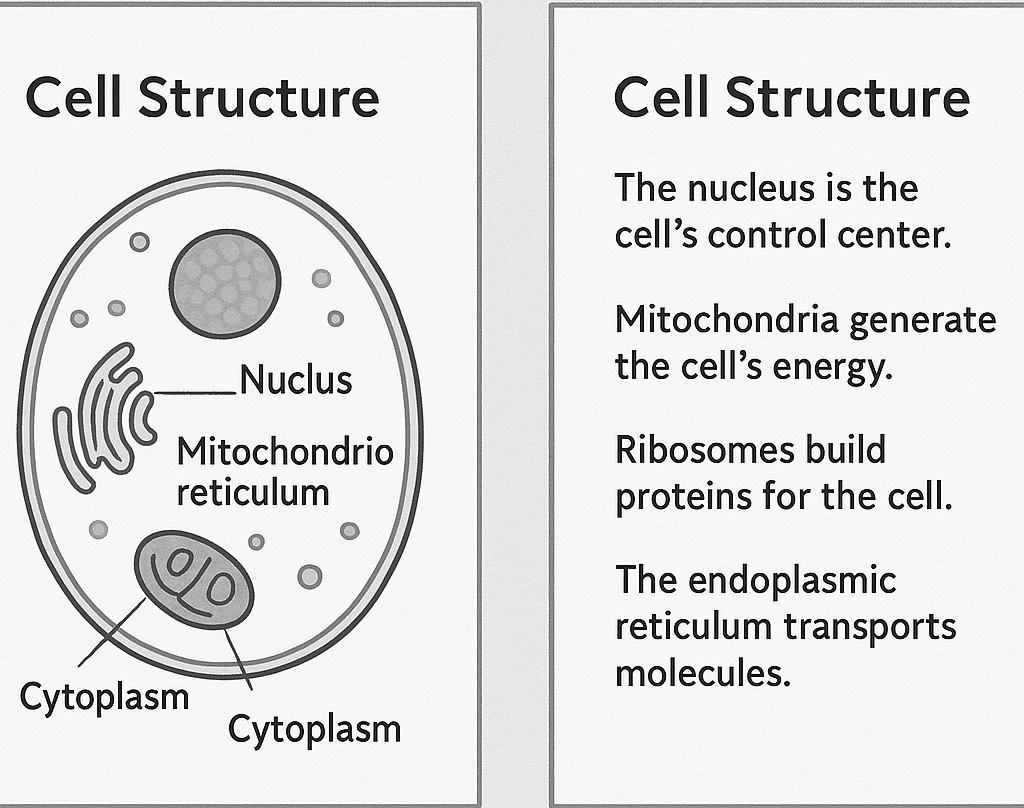

Dual coding is essentially using visuals mapped with text to enhance learning. There are rules to when this works and when it doesn’t. The problem is that some image/text combos actually make learning more difficult:

in schools, the idea often mutates lethally. It becomes:

Visuals are always good. (They aren’t.)

Every concept must include a diagram or an icon. (Most shouldn’t.)

If it looks accessible, it must be effective. (Not necessarily.)

Cartoons make content memorable. (Only if the cartoon helps you think about the content.)

Some of the examples in the article took me right back to my biology class:

It might just be anecdotal, but in the above example, I feel my brain working harder as it tries to uncouple both sets of information and hold them together in mind at the same time. For teachers, ‘drawing live’ (drawing each element as you learn about it, rather than presenting a full diagram at the start) appears to be most advantageous.

The cautionary tale, then, is simple. Every theory worth applying in schools can be misunderstood, overextended, or turned into policy by PowerPoint.

This pattern is one I’ve become familiar with in my limited foray into the world of education — grand theories that make their way into practical lessons, without scrutiny or feedback loops to understand their true impact (good or bad).

Or, in the case of handing Chromebooks to school kids, mistaking the result for the process. Digital literacy requires a broader skillset than simply using a computer, which just about any old muggle can manage these days.

So, when you’re considering adding an image to that PowerPoint, think twice:

A good image doesn’t decorate a point; it makes one. It should clarify what words alone would leave vague, reveal connections that speech obscures, and give form to the abstract. If an image doesn’t help pupils think in a way they otherwise couldn’t, it’s pointless distraction.

Read the full article here (a small section towards the end is paywalled).

Quote of the week

“The mind is a story engine, and those who learn to control it will thrive.”

— Dan Koe

That’s all for today. Have a wonderful weekend. 😊

Graham

Perhaps average Londoner is more accurate - not an average person at all!

40% of Brits haven’t read a single book in the last 12 months. (YouGov) https://yougov.co.uk/entertainment/articles/51730-40-of-britons-havent-read-a-single-book-in-the-last-12-months

If productivity is ‘being fruitful’, then phones are the most efficient way to produce fruit that doesn’t get shared. Fruit that feels good in the moment (and only for a moment). This is not so different to self-help, which provides a promised short-cut to fruit that generally speaking only benefits the self.

I've begun going to the cinema more than I used to, because it forces me to watch a film with uninterrupted focus and without the temptation of a pause button.

In general we lack the same sense of a hallowed space for reading, where distractions are socially unacceptable.

Perhaps, instead of diversifying their content and uses, libraries should offer to confiscate all media devices on entry...?